How technologically illiterate are our political leaders, and does it matter?

The digital age calls for technology aware policy makers. Digital currencies, encryption and online privacy present a few of the challenges facing governments across the world. Yet the majority of these governments are composed of those with little to no grasp of the basics of how technology works. Most politicians practical experience with technology ends with Microsoft Office. How many national leaders would understand that “Hello world!” is not the name of a prenatal meditation class, but the first step for new programmers learning a language?

Lee Hsien Loong, prime minister of Singapore, recently demonstrated that he’s the most technically literate national leader on the planet, by releasing his C++ code for a Sudoku solver. The program runs in a DOS window, in to which you enter each line of the unsolved Sudoku line by line. It then prints out the solution(s), found using a backtrack search. He even asked for users to submit bugs.

This level of know-how is above average for the general population, never mind prime ministers. But it begs the question, how do other leaders compare? And is it really necessary to have this level of technical knowledge when you’re running a country, with a number of other pressing concerns?

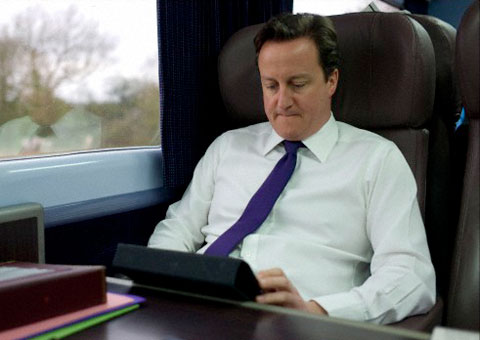

In the UK, recently re-elected David Cameron isn’t shy about speaking on technology issues; he’s boasted about the growing technology sector and advocated looser data privacy laws. He still appears to have a pretty dated view of the technology profession though.

With children learning "coding" at No 10 - being able to understand computing is vital for our economic future pic.twitter.com/yZOcHvIRcK

— David Cameron (@David_Cameron) December 8, 2014The quote marks are an embarrassing nod to an era when geek-dom wasn’t as acceptable or even fashionable as it is now. And the declaration that “understanding is vital” seems a bit hollow given that a group of schoolchildren are actively demonstrating more knowledge than him. “I know what I need to know about coding,” he told reporters. “It wasn’t completely baffling. I did understand what was going on.”

From Obama to Putin, leaders are boasting about their growing technology sectors, but none have any practical experience using the tech itself (except perhaps German Chancellor Merkel, who has a doctorate in physical chemistry, and wrote her thesis on quantum chemistry). The majority have education backgrounds in Law, or other Humanities. Merkel is a rare case of a national leader educated to a high level in the natural sciences; as far as I’m aware there have been none with a computer science education.

You might argue that political leaders are also interested in their countries agriculture and heavy industry, but we don’t expect them to start shoveling silage to get a better understanding of farmers livelihoods. But that’s exactly what they have been doing! The recent UK general election saw the chancellor, George Osborne, initiate his nationwide ‘Hard Hat tour’, supposedly to demonstrate that he’s a normal kind of bloke, but also to show voters that he understands these industries. Here’s just a selection of fancy dress options George modeled this past month,

Guy is 1of 3,450 people across Loughborough who've started an apprenticeship since 2010 pic.twitter.com/EkWMF0ppI9

— George Osborne (@George_Osborne) May 6, 2015Chef at Bikash tells me economy in a country is like Thorka in a curry, if you don't get it right nothing else works pic.twitter.com/hkZibH1NsT

— George Osborne (@George_Osborne) April 24, 2015Enjoyed meeting employees at @CarlsbergUK with our brilliant Morley&Outwood candidate @andreajenkyns pic.twitter.com/R0LPo8JIJP

— George Osborne (@George_Osborne) April 23, 2015With @John4Carlisle meeting builders who agree with me - the best time to fix the roof is when the sun is shining pic.twitter.com/hT3wy5Bfnq

— George Osborne (@George_Osborne) April 14, 2015Having a go at welding with apprentices at @HarrisPye in Vale of Glamorgan with strong local voice @aluncairns pic.twitter.com/yPB7Um2tgB

— George Osborne (@George_Osborne) April 10, 2015But why didn’t he visit any of the technology start ups that his superior has been harping on about? The only image I can find of George Osborne in even close proximity to a computer is on a visit to Warner Bros. studios, never mind using one.

It’s not as if it’s unpopular; Lee Hsien Loong has received worldwide plaudits for releasing his code, and a generation of young Singaporean voters have taken to social media to congratulate him. Perhaps national leaders are scared of alienating the majority of their voter base, who are also technically illiterate. This will inevitably have to change. If they want to inspire young people to get involved with technology, and win a few younger voters along the way as well, politicians should be encouraged to get their hands dirty. If they’re making big decisions about net neutrality and digital currencies, a little low level experience playing with the cogs and gears of the internet won’t do any harm. We certainly don’t expect or even wish our leaders to become expert hackers overnight, but a little practical exposure could go a long way to resolving some of the dangerous misconceptions about technology often held by some of the most powerful in our society. At the very least, the next time a bunch of tech savvy school children turn up at David’s house, he could speak the same language.

Subscribe via RSS