Favourite readings of 2016

Here’s my (belated) list of top reads from 2016, in no particular order. None of them were released in 2016, so if you’re looking for the latest hits, best look elsewhere. There’s autobiography, biography, graphic novel, philosophy, and a generous helping of science fiction. Enjoy!

Ursula K. Le Guin - The Left Hand of Darkness

Le Guin has been high on my to-read list for a long time, and this year I finally sat down with what is widely regarded as her most accomplished piece. The Left Hand of Darkness is more of a fantasy story than a sci-fi, but the USP is exactly the kind of experimental feature synonymous with sci-fi. On the technologically impoverished world of Winter, the inhabitants can change gender as they wish. It is with this fascinating plot device that Le Guin turns a mirror on our own ideas of gender, and gendered society, through the eyes of a male ambassador from another planet. His initial reservations and culture shock are profound.

“A man wants his virility regarded, a woman wants her femininity appreciated, however indirect and subtle the indications of regard and appreciation. On Winter they will not exist. One is respected and judged only as a human being. It is an appalling experience.”

Bryan McGee - The Great Philosophers

I picked this up in a charity shop as I’ve been hankering for an introductory history of philosophy, and I’m so glad that I did. The reader is taken on a chronological journey from the pre-socratic greek philosophers up to the analytical philosophers of the 20th century, each chapter dedicated to one or two of the most important philosophers from a given period. What makes the book unique is the format of each chapter: Bryan McGee invites an emminent philosopher on the subject in for a chat, and they proceed to have a ‘socratic-dialogue’ on the philosopher or philosophies in question. All these interviews are available online, and are transcribed verbatim here, which proves useful when they delve in to the detail and you need a little extra time to wrap your head around the concepts.

“No one has any difficulty, he said, in understanding that a person has a passionate love of nature, yet we should consider such a person mad if he wanted nature to love him back. Now because nature and God are one and the same, the same thing is true about God. It is conducive to our happiness to love God, but meaningless and absurd for us to expect God to love us.” - McGee on Spinoza

McGee, an ex-Tory MP and populiser of philosophy, is a wonderfully enthusiastic and knowledgeable host, and expertly guides the conversation. He always pushes his interviewees to make their analysis as understandable to the layman as possible, an often difficult proposition given the subject.

Ernest Hemingway - A Farewell To Arms

My first exposure to Hemingway, Fiesta / The Sun Also Rises, was slightly disappointing. I couldn’t get behind any of the self-centred, mean spirited (and sometimes anti-semitic) characters, and Hemingway’s prose didn’t leave much room for them to hide. In A Farewell To Arms though, an autobiographical account of Hemingway’s role as a volunteer ambulance driver on the italian front during the First World War, I had no such qualms. There are many fascinating characters making their way in a country in conflict, and Hemingway’s sparse, honest prose reveals more than it hides. It is an addicting, heart renching and * spoiler alert * ultimately tragic book.

Mikhail Bulgakov - The Master and Margarita

I’m pretty ignorant when it comes to Russian literature, but I recognised the name Bulgakov when I picked this up in a charity shop, and was intrigued by the cover. It’s a satirical raunch through soviet Moscow, featuring the devil and his entourage, including a giant, black, talking cat. Managed to finish the majority of this in a few overnight train rides through Vietnam, so my memories of this novel will always be mixed up with the smell of Pho and stale sweat.

My copy was an early translation, though from reading around there appear to be more recent translations that capture the comedy better - if you’re keen, seek out one of these translations.

Carl Sagan - Contact

Another tick off the must-read list, and my first Sagan novel. Contact is the story of, well, first contact with an extraterrestrial civilization. The protagonist is an exceptionally bright female radio astronomer, who encounters all of the hurdles one has, depressingly, come to expect a female scientist to encounter in her career in the 20th century (and must still face in many institutions today). When she becomes one of the first people to observe a mysterious signal, she must double down on her reputation and life’s work in the face of hostility from colleagues, religous fundamentalists and sceptical government officials.

Definitely worth a read, even if you’ve already seen the slightly disappointing film.

Daniel Keyes - Flowers for Algernon

One of the few books that has made me openly weep, Flowers for Algernon is the heart-rending, tragic tale of Algernon and Charlie Gordon, both the subjects of a ground breaking experiment to increase intelligence. The eponymous Algernon is a lab mouse, who is subject to the experiment first, and initially appears a great success. Charlie, who suffers from Phenylketonuria, which manifests as a severe intellectual disability, is the first human subject.

The novel is written in the form of a diary by Charlie. The prose begins jilted, strewn with spelling and grammar mistakes, but Keyes takes care not to make it crass. As the experiment takes effect, the writing improves in parallel with his increasing intelligence. It also leads him to question the loyalty of his old acquaintances, and in time the scientists who started the experiment on him, which leads to bitter conflict and acrimony.

I don’t wish to reveal any spoilers, so I will only say that the ending is one of the most heartbreaking of any story I’ve ever read. Now to watch the Oscar nominated film based on the novel…

Kate Evans - Red Rosa

Rosa Luxembourg, 1871-1919, was an economist and revolutionary socialist intellectual from Poland, who established herself in the the German political scene after exile from her homeland in the early 20th century. During this time intellectual, strong minded women were not typically welcome in the pervading patriarchical society, and she encountered many hurdles. Her story is ultimately tragic, but her work has lived on, and her name has become a rallying cry for socialist causes around the world.

‘I want to affect people like a clap of thunder, to inflame their minds with the breadth of my vision, the strength of my conviction and the power of my expression’

Kate Evans illustration is unique and magical, brilliantly capturing Rosa’s humour and humanity. Her love life is covered with affection, but does not dominate the book (the author breaks the third wall at one point to declare that she will no longer include Rosa’s love life in the narrative, and focus on her politics, noting that women are not defined through their relationships to men).

“There are two sorts of living organisms.. those who have a backbone and therefore also walk, at times even run, and others who don’t have one, and therefore only creep and cling”

James Harford - Korolev

If you’re a space race nerd like myself, this is required reading on one of the biggest characters in the whole saga. Sergei Korolev was the charismatic ‘Chief Designer’ in the Soviet space program during its early phenomenal successes. He personally oversaw the launch into space of the first animal, the dog Laika, and the first man, Yuri Gagrin, as well as the first spacewalk by Alexey Leonov. He was also integral to the development of Soviet missile and spy satellite operations.

Harford, a former senior member of NASA, has comprehensively researched the history and contributions of this remarkable man, dilligently sifting through the masses of disorganised documentation from the Soviet years, including original Russian manuscripts. He takes great care not to idealize or embellish the narrative, and seeks a huge range of sources, interviewing former colleagues and family.

Korolev tragically died during a routine operation in 1966. At this point the American space program was beginning to overtake the Soviet, due to a combination of underinvestment and poor planning from the overarching Soviet organisational apparatus. It was this same ideological behemoth that Korolev had been fighting all his life - he was imprisoned by the NKVD in his 20s and sent to the Gulag during the infamous Stalinist purges. Korolev’s life was coincident with many of the most (in)famous moments in 20th century history, and is part of what makes him such a fascinating character to learn about.

Stephen Webb - If The Universe Is Teeming With Aliens … Where is Everybody?

The Fermi Paradox is the subject of this comprehensive analysis by Webb. The paradox is named after Enrico Fermi, an Italian physicist who, when working in the US in the 1950’s posed the question, ‘Where is everybody?’. He was, of course, referring to the lack of contact with extraterrestrial civilizations. If there are billions of stars in the galaxy, and some of these stars have Earth like planets that develop life, and some of this life becomes intelligent and travels in to the cosmos, then, assuming modest probabilities for each of these steps, the galaxy should have been comprehensively conquered by intelligent beings by now and, most importantly, we should have seen some evidence of this.

The book takes the form of 75 solutions to the paradox, ranging from the comedic (they are here, and they’re called politicians!) through to the latest astrobiological predictions for how common the emergence of life from pre-biotic materials is. Webb is a light hearted narrator, and each solution comes with his personal take. The format might not be for everyone, but I found it incredibly enjoyable and stimulating, and expect to return to it often in the future.

‘The planetarium hypothesis taken to extreme is similar to solipsism. The true solipsist believes that everything he experiences.. is part of the content of his consciousness, rather than an external reality in which we all share… The true solipsist when defending his philosophy presumably has to inform his opponents that they don’t exist, which seems a rather ludicrous thing to do’

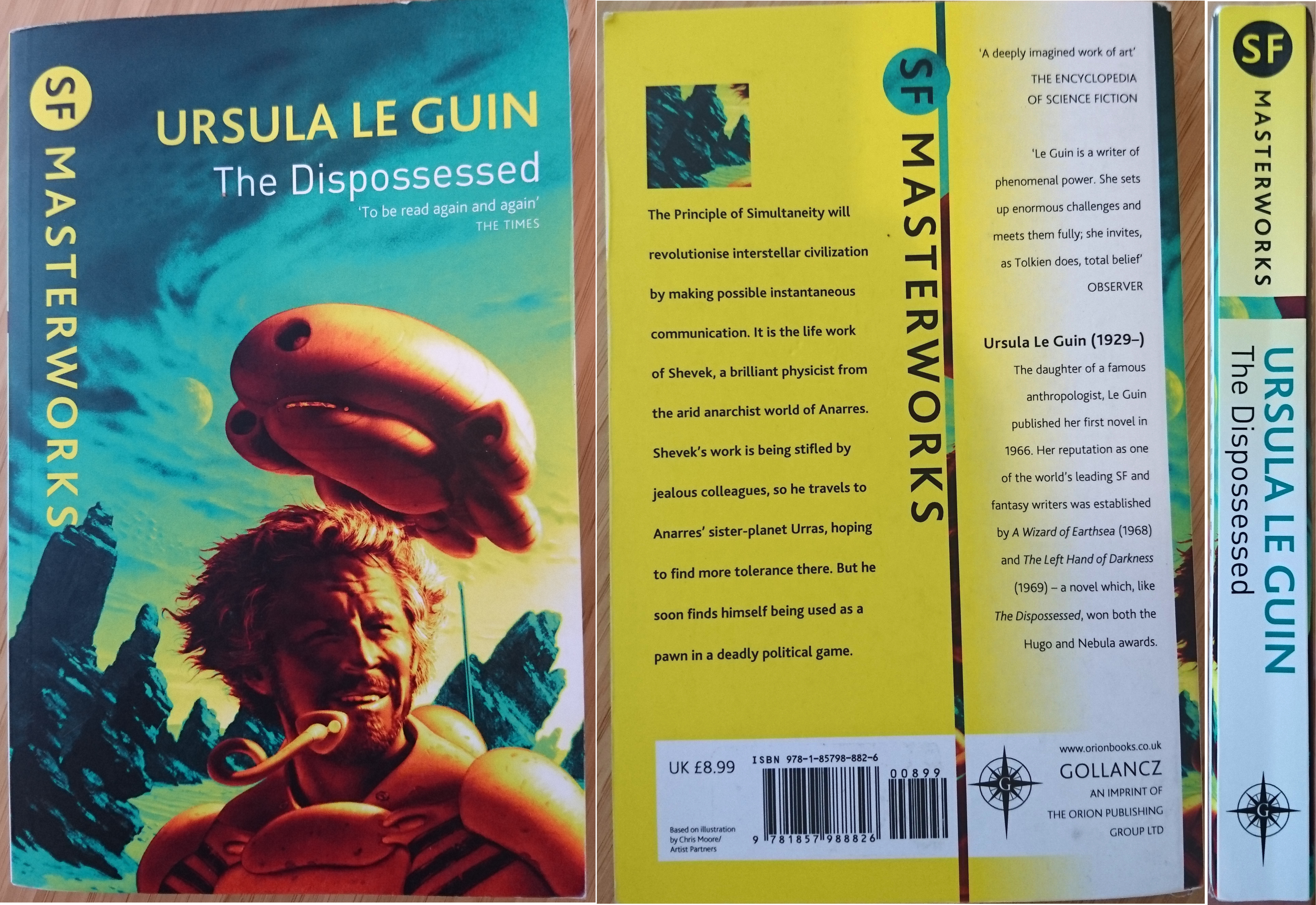

Ursula K. Le Guin - The Dispossesed

And finally, my favourite book of the year. Another Le Guin novel, arguably better than Left Hand of Darkness, but I couldn’t leave either off this list. The Dispossesed is the story of Shevek, a brilliant physicist from the anarchist socialist world of Anarres, who travels to the neighbouring liberal, hyper-capitalist world of Urras in order to complete his life work on The Principle of Simultaneity. His trip is also a personal crusade to bring the two worlds, who share an antagonistic history, closer together, but he soon finds himself being manipulated by forces beyond his control, and doubting the very purpose of his trip.

The first thing to appreciate with this book is how believable the world is. Le Guin has crafted a history, a politics and a sociology that is at once completely alien yet wholely conceivable. There’s little moralising: both systems are prodded and tested, their merits and failures explored through a host of compelling yet flawed characters. Here’s one of many quotable passages, this a humourous one on Urrastian capitalist economics:

“He tried to read an elementary economics text; it bored him past endurance, it was like listening to somebody interminably recounting a long and stupid dream. He could not force himself to understand how banks functioned and so forth, because all the operations of capitalism were as meaningless to him as the rites of a primitive religion, as barbaric, as elaborate, and as unnecessary”

I cannot recommend this book enough. Don’t be put off by the gaudy science fiction covers. If you like a book that makes you think and question the world around you, give it a chance, and you’ll be blown away.

“The sunlights differ, but there is only one darkness”

Subscribe via RSS