How to build a galaxy, #1

In just two weeks I’ll begin my Ph.D., and after attending the STFC summer school program last week I’m now feeling very inspired and eager to start. In the run up I thought it would be quite fun (?) to write a few short posts on some of the work that went in to my 3rd and 4th year projects during my integrated masters. This post introduces my third year project titled “Star Formation Epidemics in Galaxies”, supervised by Professor Anthony Whitworth and Dr Dimitris Stamatellos (Anthony unfortunately fell seriously ill at the beginning of the project, but Dimitris bravely stepped up whilst he recovered to help me and two other students. I’ve since learned at the summer school that Dimitris is supervising one of my fellow Ph.D. entrants, so congratulations and best of luck to them both!).

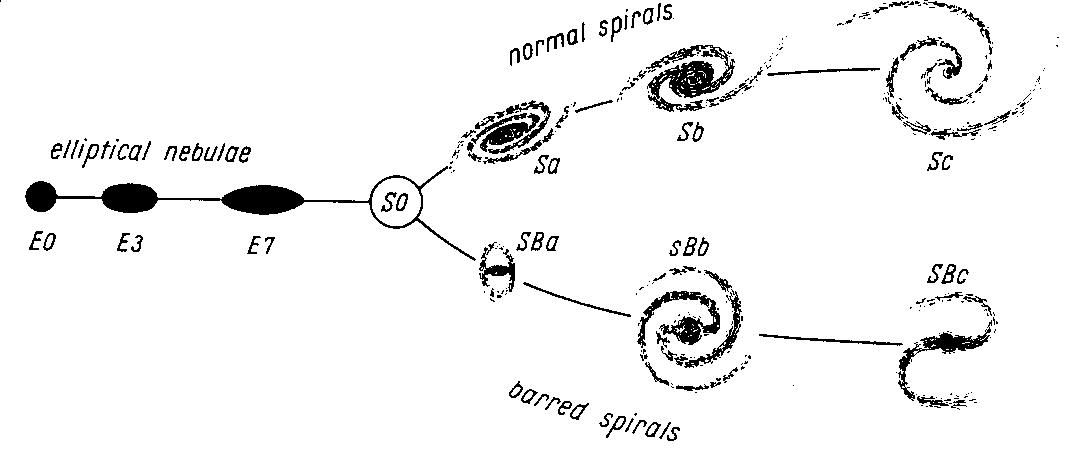

The aim of the project was to model a galaxy, simulate it, and test the outputs of the simulation against observed galaxy properties. Galaxies display a wide range of morphologies, and many attempts have been made to classify them based on their appearance. The most well known galaxy morphology classification system is the Hubble sequence, also known as the ‘tuning fork’ diagram due to its shape.

At the far left of the diagram lie the elliptical galaxies, collections of old stars that appear as uniform spheres on the sky. To the far right of each end of the forks are the spiral galaxies, flat dusty galaxies with large spiral arms. The fork defines whether the spiral has a central bar or not, a feature seen in a large proportion of spiral galaxies; our own Milky Way galaxy is in fact a barred spiral. This classification scheme has remained remarkably popular, especially given that it’s mostly unrelated to the underlying physics which leads to these variations in appearance.

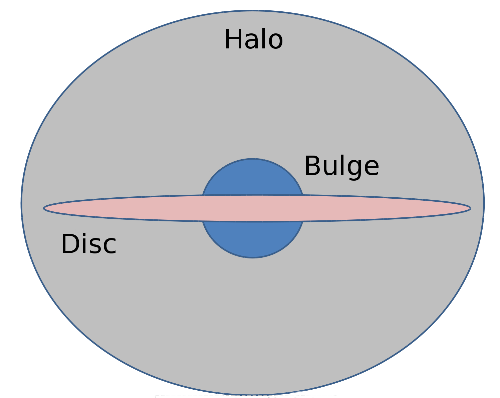

My task was to create a spiral galaxy, and one of the first ingredients required was a model of the gravity on large scales, due to all the stuff in it. Spiral galaxies have two distinct visible components that provide this gravity. The first is the bulge, a spherical distribution of older stars around the center. The second is the disc, a flat pancake of stars, gas and dust on which the spiral is visible, and is usually where star formation occurs. However, with just these two components we have a problem: The velocity of material spinning around the galaxy should decrease with radius, according to Newtonian dynamics,

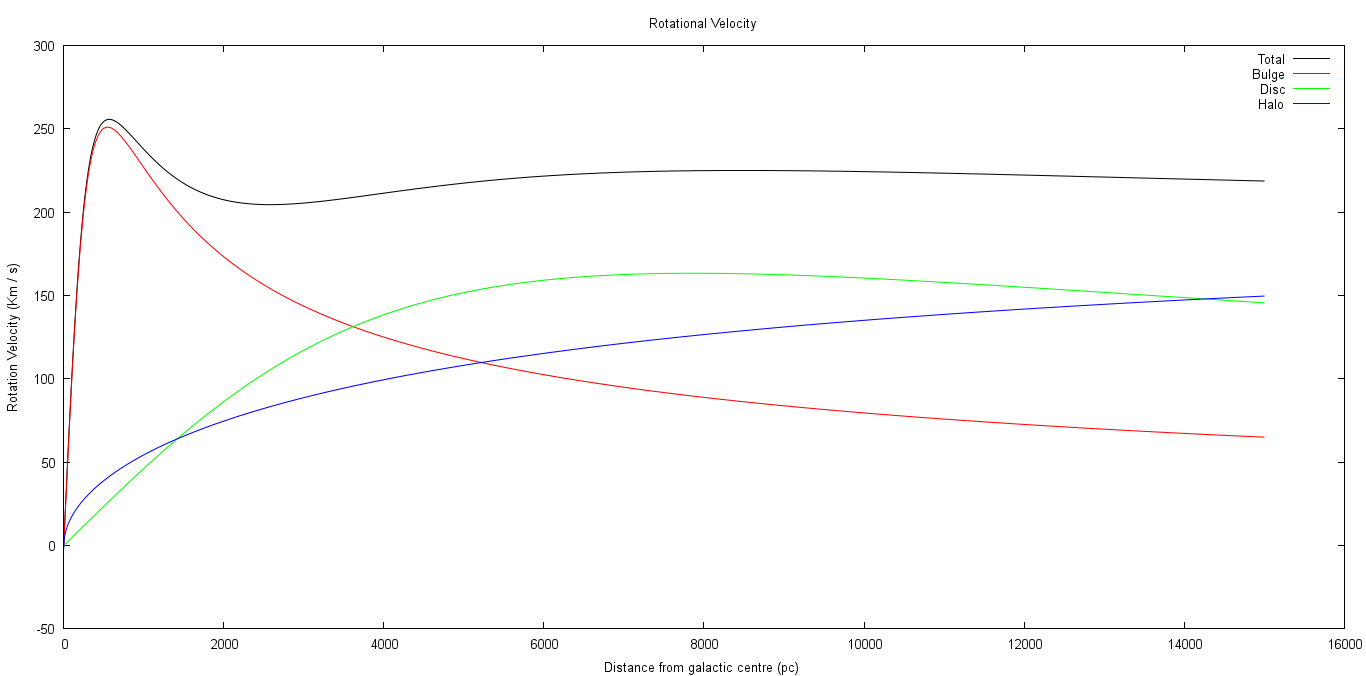

However, this is not what’s observed; in fact, the velocity remains relatively constant with radius. This presented a major problem to theorists in the mid-twentieth century: could Newtonian gravity be wrong at these great distances? Or was there new physics causing the discrepancy?

One of the first astronomers to observe these rotation curves was the American Vera Rubin. In particular, her and her co-author Kent Ford in 1975 stated the bold implication that this could be due to mass further out than the stars. Further work found that this made up matter at large radii, if arranged as a halo around the galaxy, could accurately replicate the rotation curves observed. It provide the extra gravity needed to give particles far from the galactic centre the extra velocity observed in actual galaxies. This extra matter is now well known as Dark Matter… physicists still don’t know what it is, but it makes for good galaxy models!

With this dark matter halo, the rotation curve now appears as it should. You can see the contributions from each of the components below, as well as the combined rotation curve,

Now that we have a galactic gravitational potential that produces realistic rotation curves, we can start putting things in to it. In the next ‘episode’ I’ll add molecular clouds, and describe how we can model star formation through the energetic collisions of these clouds.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: