Topic modelling No.10's speeches

If you just want to play with pretty interactive things, scroll down and click on the image. Once you’ve finished, come back and humour me by reading the rest

Computational text analysis is a rapidly growing field of research that promises to extract meaningful information from one of the most abundant and fundamentally unstructured data sources that humans produce.

To understand a body of text you have to read it - however, getting computers to do some of the reading for you is not only (a lot) quicker, but can also uncover hidden patterns in the structure of the text that you, as an inconsistent, blind, blundering and fallible human, wouldn’t.

One such method of text analysis is topic modelling, which seeks to reveal the underlying topics being discussed in a collection of texts. In this context, a topic is just a collection of words that are related - for example, the words car, train, boat and plane could all be members of a topic called “transport”. Similarly, you could have another topic, “exercise”, that contains the words run, marathon and train. Notice that the word train can appear in more than one topic - it is a homograph, i.e. a word that is spelt the same but has a different meaning. One for your next pub quiz.

The algorithm I’ll demonstrate here is called Latent Dirichlet Allocation. It works by looking at a collection of documents and searching for terms that co-occur within a document frequently. So, if the terms cat and dog appeared together in multiple documents, but rarely appeared on their own, the algorithm would identify this and group them in to a topic. It also allows terms to be included in multiple topics, necessary if you have homograph’s as above.

A key feature of the algorithm is that it requires no information on the collection of documents being studied - it simply looks at the distribution of terms and groups them together in to as many topics as you specify up front. The output is then a list of terms for each topic, but with no labels - the algorithm doesn’t know what a topic should be called, as it doesn’t really care about the meaning behind the words used.

To demonstrate, I’ve downloaded all of the official speeches published by No.10 during the coalition years, 2010 to 2015, from data.gov (see here) using import.io for the data retrieval. There are over 450 speeches, covering a huge range of topics, and often multiple topics are discussed within a single speech.

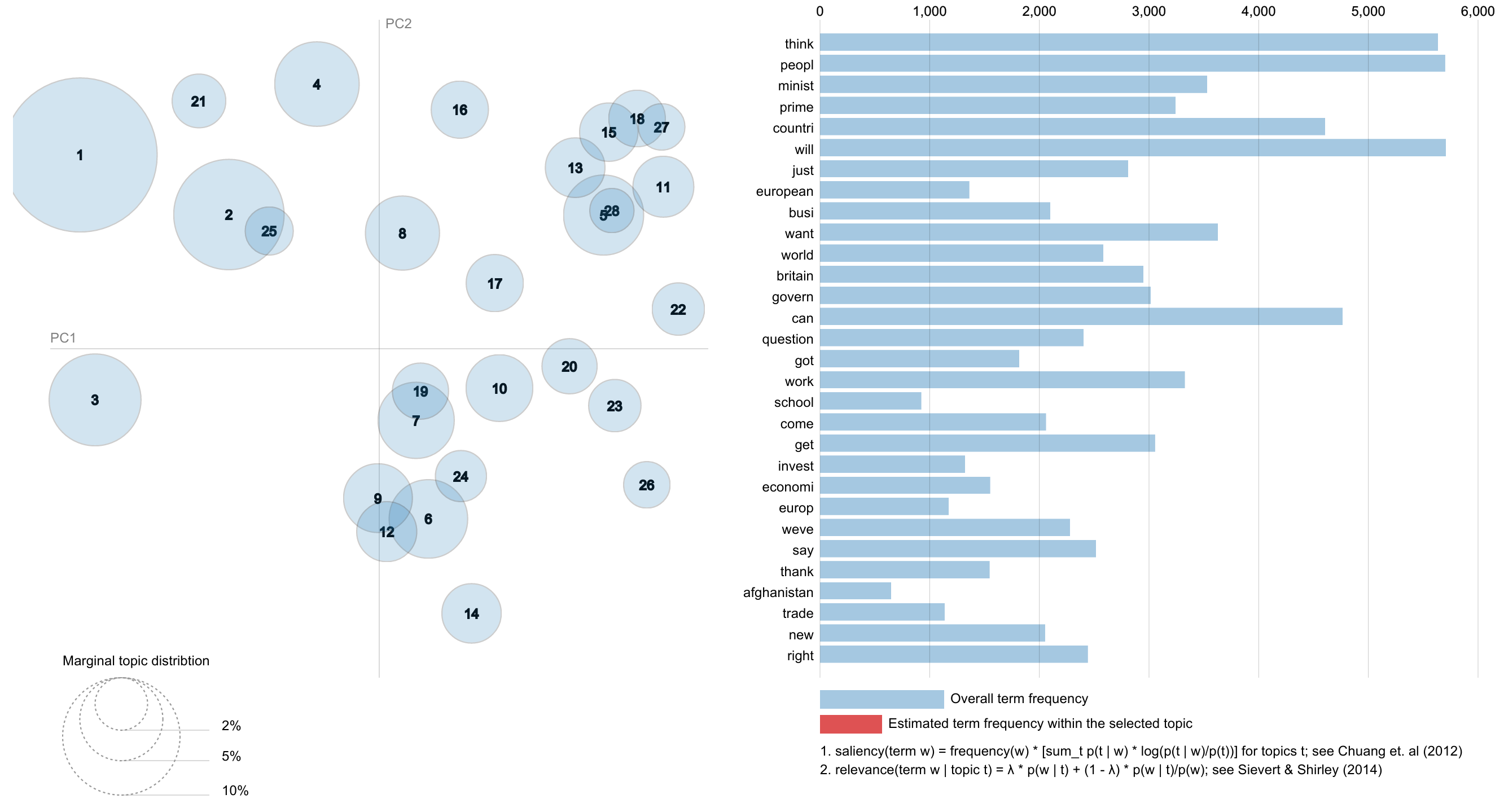

Click the image below to link to a visualisation of the output of a 28 topic model run on the speeches. Before going any further, first set the slider at the top right of the visualisation to 0.6. I’ll explain at the end of this post, if you’re interested*.

The plot to the left shows each of the topics reduced to their first two principle components - if you don’t know what this means, don’t worry, it’s just a way of showing how similar two topics are, distilled down to two dimensions. So where the bubbles overlap, these topics should be quite similar.

If you click on Next Topic at the top, the first topic should be highlighted. This changes the list of words to the right. Each word here is part of the topic, sorted by their importance to that particular topic. You might notice that some of the words look a little strange - minist for example. This is due to a process called stemming that I apply to the documents. This shortens words down to their root, so in the example above minist could have been minister, ministers or ministerial. The reason for this is that the topic model will not be able to identify that these words are all essentially talking about the same thing. Stemming allows us to gather similar words together, so that the topic model can do its thing more effectively.

You can also highlight terms to see which topics they are a part of. The size of the bubble shows the number of occurrences in that particular topic.

The first two topics are pretty dull - they contain very general terms used by the prime minister in his speeches. I have tried to clean some of these out (using a common stop word list, and filtering terms with a low term frequency / inverse document frequency score), but this turned out to be difficult without losing relevant content. From topic 3 onwards though things get pretty interesting.

I’ll highlight some of the most interesting patterns I’ve found. First there is topic 5, which seems to be about the Eurozone and Britains part in it. Many of the countries that experienced economic difficulties are mentioned too. Completely within this, and therefore closely related, is topic 28, which talks about Northern Ireland. The language used when discussing these two topics must be very similar - the way that the similarity is calculated here looks at all of the words assigned to the topics.

Topic 6 is a big one, about Finance. There’s a mix of terms about the deficit, debt and spending, but also terms about banks, and the interest rate (presumably discussed alongside a particular Bank I’m quite familiar with). The 3 nearest topics to this one are telling - 24, 9 & 12 are about the NHS, welfare/benefits and the ‘big society’, respectively. Evidently, any discussion about these topics was closely followed by talk on their costs.

Topic 11 mentions countries that participated in two of the major conflicts over this period, Russia & Ukraine, and Syria. The fact that these two conflicts are discussed in very similar terms perhaps reflects something of the similarity in there fall out. Both were initiated by popular protests that ended bloodily, and both descended in to protracted, confusing civil wars with significant outside influence.

Topic 16 is an interesting one, that appears to be associated with remembering past conflicts. There is also mention of Margaret Thatcher, so perhaps it is a more general topic about remembering the past. By specifying more topics up front we could perhaps tease out two topics from this single one, however this would also dilute the amount of content in each topic.

Finally, there are four overlapping topics in the top right corner, 13, 15, 18 & 27, that are about Islamic extremism, the Libyan conflict, Afghanistan and a general topic about the frustrating lack of peace in the middle east, respectively. The fact that these are all distinguishable in to separate topics shows something of the amount of time that has been devoted to these issues in speeches from the prime ministers office, and their impact on British politics over this period.

Interesting stuff! and powerful - to read these topics and communicate the content in such a consumable, quantitative way by hand would we impossible. The data generated here can be related back to the original documents too, to show how much of a particular topic is mentioned in a given speech; this is very useful for classifying documents.

If I get time I’ll add some extra features to the vis so that you can do just that, and also see the speeches themselves, to assess whether you agree with the algorithm.

*The relevance metric has an impact on the sorting of the terms. It is a weighting term, adjusting the relative frequency of a word in a topic as compared to in the whole collection of documents. You can see the difference by moving the slider to the extremes - when lambda is one, the most frequent terms in the topic are shown, whereas for lambda equal to zero those terms that are used mostly in this topic are weighted highest.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: